The Russian Painter

Artemis fled a war, fought a felony, and spent 10 months in ICE captivity. It's a good thing he can paint.

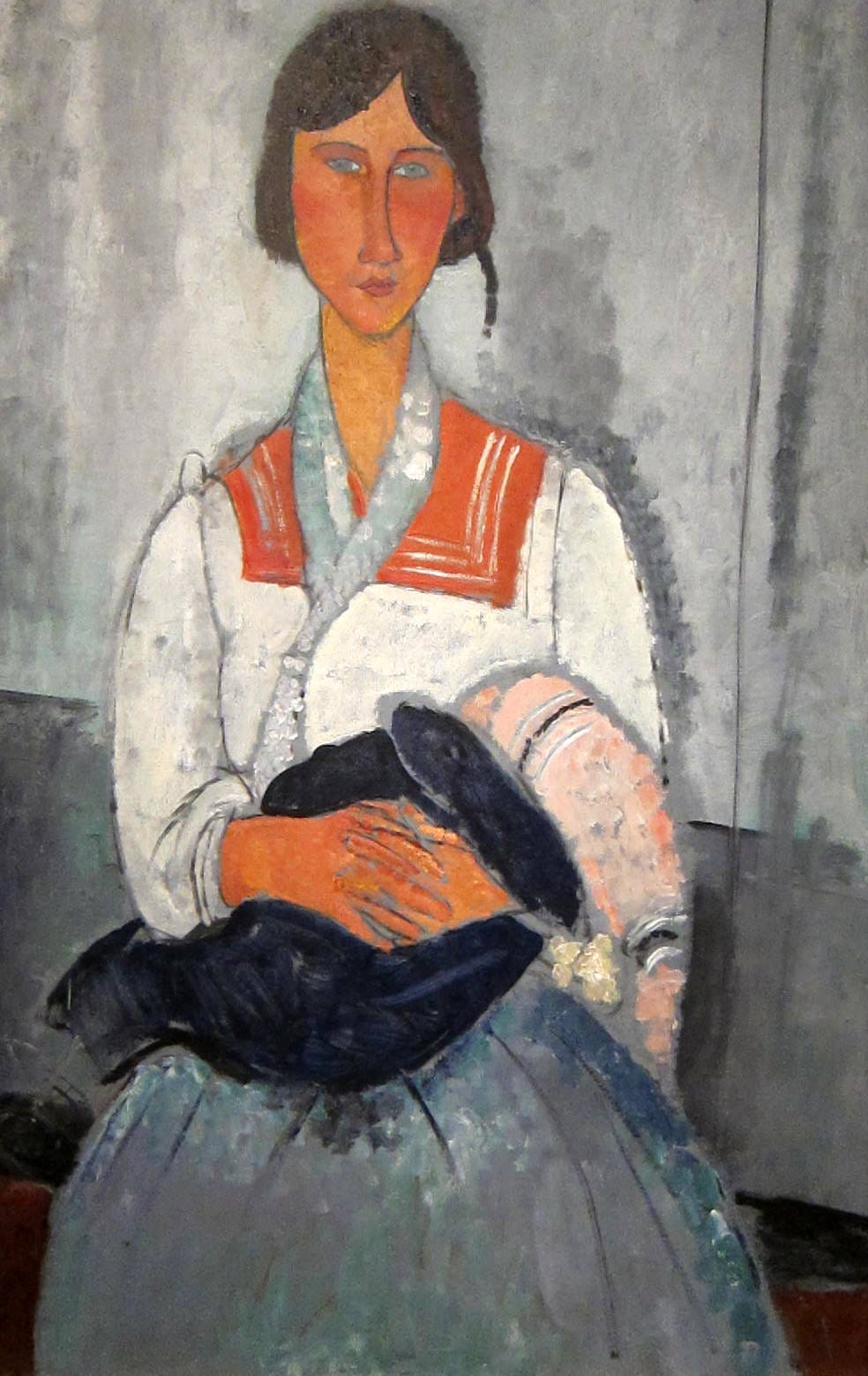

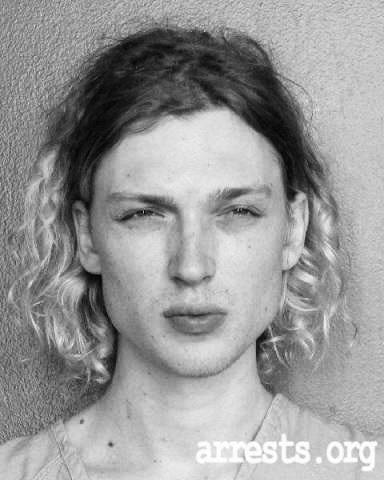

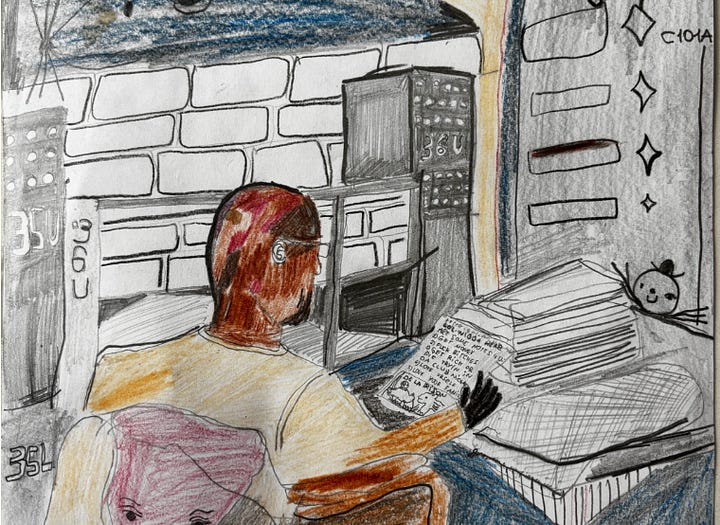

On a strip of 6x6 cloth nailed to a wall, dozens of abstracted bodies congregate on a grey floor. Some lie on cots, others sit together at a table, and someone in the bottom-right corner screams with hands held high. The deranged painting, made with acrylic and charcoal, is called “Common Cell Room.” It depicts living conditions in the Moshannon Valley Processing Center, the largest ICE detention facility in the northeast. Its creator, a Targaryen-looking 28 year-old, makes sure to point out a fallacy in the building’s name: “It is not a processing center. It is a prison.”

The MVPC, per his description, is a shipping container that holds 60-70 men in the same open area. There are no cells; it’s just one big dusty pod. All within it are immigrants without enough documentation to appease the insatiable Trump administration. Some have criminal histories–murderers, drug-dealers, petty thieves–but many are innocent, harmless, asylum-seeking people who have found themselves trapped in the Middle of Nowhere, Pennsylvania, because of a nightmarish turn of events, both in their home countries, and the one they sought refuge in.

There have been substantial reports of physical and psychological abuse by guards. Namely chokeslams, spitting in the faces of detainees, the withholding of food and water, and illicit discrimination towards non-English speakers. Last August, three people were stabbed with a shank by a fellow inmate. Just three weeks ago, a Chinese citizen awaiting a hearing was found hanging dead in the shower.

Artemis recently spent 10 months there.

Shortly after his release, we met at an art studio in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. It was a bright Sunday afternoon and we were the only ones in the building. His allotted plot was ripe with coconut water, Pelligrino, fresh fruit, scattered tubes of paint and brushes, a few large-scale canvas’ hanging from the wall, and thick stacks of sketches he drew while in ICE custody. At first, his demeanor was calm, his speech thoughtful. I was surprised to hear him liken MVPC to an involuntary, and far less serene, ashram–a spiritual retreat popular among Buddhists for intense inward reflection.

“I tried to find the divine in everything,” he said in his thick Russian accent, “and this helped me a lot. I was optimistic all the time. I had no other choice. If you’re there and not optimistic, you are dying.”

When speaking about “Common Cell Room,” his tone flipped. His eyes got twice as big and his voice tensed with frustration while pointing hard at areas of the painting: “One row, two row, three row, four row, 60 people, one big common room. Always phone calls, always fights in the bathroom, people taking shits, fights over the microwave…Listen, see this,” he jabs his finger on a figure in red slouched down, “they use a piece of the dice tube, this one crazy person from El Salvador, a real thug, he was scraping the dice tube on the floor every day to sharpen it. Everyday, day and night, nonstop. He made money from it.”

“The murderers,” he continued, “were the nicest people. The biggest drug dealers, they were such genuine, gentle people. Those people who were doing small crimes were stupid, low intellect, ill-mannered, loud and obnoxious. We were all living in a fucking zoo. It was so intensively bad. It was pure fucking hell, my brother, it was so wicked bad.”

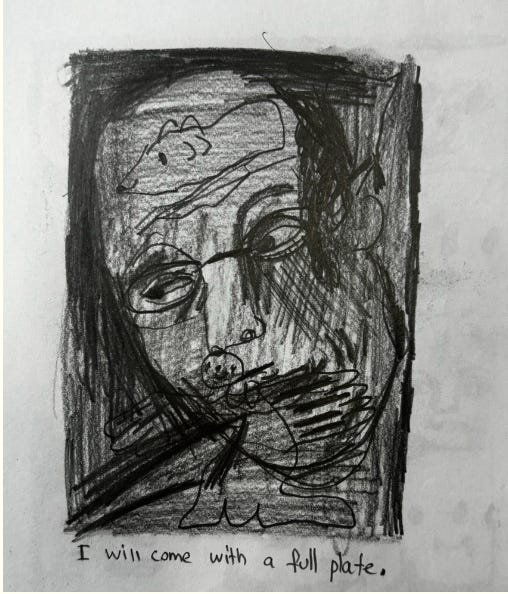

He kept himself occupied by reading Kafka, playing chess, praying, and obsessively sketching. “I was drawing scenes from our life,” he said, “and they [other inmates] were like, ‘Oh, look, look, it’s me, it’s me.’ In the evenings they looked through my drawings. It was entertaining for us.”

Artemis is not a famous painter. He is known by some curators and collectors, but subsists on his entranced work ethic, inordinate style, and occasional modeling gigs. His art blends purity with the abrasiveness of reality; it’s like something out of a demented toddler’s daydream. He uses vibrant colors on tragic figures, hides good and evil in between what may look like unintelligible scribbling, and is wholly absorbent of however his fortunes unfold. He has an intense, at times unnerving presence, punctuated by sea green eyes that burn through you. There’s a persuasion to his mannerisms that I’ve only found among truly possessed artists, who, for whatever reason, often fly too close to the sun.

During our two hours of conversation, Artemis would appear stoic, talking about divinity and the treasured friends he made while locked up, then in the next moment radiate with intoxicating emotion while telling a story, no matter how riveting or insignificant its content actually was. It’s as if an internal pendulum would not stop swinging. Given the sheer insanity of the past five years of his life, solid ground has not only been hard to come by: it’s become nearly impossible to trust.

There is a place in the center of Moscow called the Lanceray House. It is an eight-floor, neo-Gothic building that was utilized during the October Revolution of 1917, where the Bolsheviks’ Red Guards fired countless rounds of artillery from its scaffolding. After its construction, destruction, then reconstruction, it became what we here in America would call a shared living space. A more astute comparison may be a dirtier–and much less publicized–version of the Chelsea Hotel.

In the last decade of his life, painter and sculptor Eugene Lanceray lived in one of the building's apartments. He is now considered a hero in Russian art for both documenting the aftermath of Lenin’s victory and painting an astounding mural in Moscow’s Kazansky train station.

Nearly a century after his passing, the Lanceray House remains a solace for bohemian classes of artists. It’s a place where musicians, architects, playwrights, and painters alike live and breathe their own, and each other’s, work. While attending Gubkin Russian State University in the late 2010s, Artemis Lyiskov visited with some friends, and was struck by how its interior decay was contrasted by the liveliness of the artists who inhabited it. The building cast a spell, causing the promising student to move in and radically redirect his life towards whatever the energy oozing out of that building was.

See, he was supposed to be a chemist. Raised in St. Petersburg, he grew up attending a school for those gifted in science, then headed to his country’s capital city to obtain his degree. He was a dedicated student, winning Science Olympiad contests in high school and working in a research laboratory while in Moscow. He had always doodled in class, but didn’t give much consideration to visual art as a legitimate path.

But upon entering the membrane of the Lanceray House, Artemis was simultaneously introduced to the Moscow creative scene. He befriended artists, hung out in their studios, and tagged along with them to exhibitions around the city. One painter in particular, from Monteparnasse, Paris, took him to an exhibit featuring the work of Amedeo Modigliani, a boundary-pushing traditionalist from Tuscany. The poetry in Modigliani’s work was a flashbulb moment. Artemis decided it was time to take the leap.

He took a trip to Beijing, bought charcoal and oil pastels, and began his first painting. It was of a Chinese girl carrying a goldfish in a plastic bag—no doubt in the vein of Modigliani, whose subjects were often pedestrian. After this, the itch became unscratchable. He devoted himself to art, and within a few years, things had begun to snowball: a move to Istanbul led to the sale of a few paintings, these sales led to trips across Europe, these trips led to handshakes and exhibition invites, and the culmination led Artemis to embark on his nomadic ways. The important thing to note is that this country-hopping only began as voluntary.

In the winter of 2022, after a stint in Spain, Artemis returned to Russia. It was not long until the Putin administration launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, attacking their military strongholds and air defense systems with missiles launched onto multiple fronts. Artemis, like many peers at risk of being drafted, chose to flee. Because of this resistance to fighting, paired with previous troubles he faced with the government1, he escaped by stealthily crossing the Belarus border, eventually making his way back towards Istanbul, where he had some friends. From there, he embarked on what he calls a “war trip” across six countries, culminating in Athens, Greece. As the self-mythologizing Artemis tells it, while standing at the feet of Athena’s statue as the wind blew west, he decided it was time to cross the Atlantic.

His first stop was Bogotá, Colombia, where he stayed for two weeks before heading to Mexico City. There, he took residence in Polanco, a luxurious neighborhood teeming with art galleries. He spent a productive year in CDMX, which he calls a “beautiful city,” but ultimately knew that he wanted to end up in New York. He had a Russian Passport, a Mexican driver’s license, and some money in the bank from years of art sales. The details of his travel are blurry, but what I do know is this: he took a flight to San Diego, a bus to Los Angeles, then another flight to New York City, where he did not know a soul.

The adjustment was disheartening. He was a visa-less war deserter bouncing around from murky-building to murkier-building in a city that American citizens with stable jobs have trouble moving to, all the while haunted by nightmares of being tracked down by the Russian government, or his family paying the price for his disappearance. Overseas, the war raged on, and any hope he might’ve had of returning to his home country diminished with each mortar that fell.

“It was uncomfortable,” he said of his first year in New York. “I changed so many houses.” He likened the environment of one in particular to the Stanford Prison Experiment: “Even good people can become evil. This is what happened to these people.”

I first met Artemis on August 23rd, 2023, at a subterranean nightclub in Lower Manhattan. I was standing by my girlfriend’s side as she smoked on the stairs, and a sinewy man of about 6’3” with long silver hair asked me for a hit. I was not smoking, nor was it my joint, but I arranged an agreement that left all parties happy: a hit of my girlfriend’s joint for a hit of his watermelon Geek Bar. He took a big rip and she warned him: “careful, it’s hash.” He didn’t seem to know what this meant, but he clearly loved the taste. When I asked him what he did, he said in his baritone accent, “I am an artiste.” I asked what type of art: “moderne.” We followed each other on Instagram and parted ways. Later that night, we saw him dancing, his head bobbing above the rest, nearly hitting the low ceiling, and he thanked my girlfriend for the hash. He struck me as goofy, eccentric, and dead serious all the same.

I didn’t think much of him over the next few months, until he began manically posting stories on Instagram in early 2024. These were mainly videos of him smoking cigarettes and drinking liquor while working on his art or walking around Manhattan, usually with Russian or Atlanta rap playing in the background. Then came a trip to Miami, followed by cryptic messages about a possible arrest, silence for a week, a video of him back in New York with an ankle monitor on, and finally, a post on his account made by someone else explaining that Artemis had been taken into ICE custody. The few updates over the next 10 months offered little explanation about the situation. He started posting again when was free and back in New York. That’s when I reached out for an interview.

As he tells it, it all started with a “misunderstanding.”

“It was a car chase in Miami and everything looked like I kidnapped her, but I did not. Lots of girls, lots of people. They were fighting with me. I was driving a convertible car, a red convertible car, a moose-tang. The chick was a hot blonde girl, and it looked like I put her in the car and closed the door. Everybody was yelling. Everybody was like ‘Hey! Hey! Let her go!’ But she ran to my car because I was chasing another car. She came with some dude, and I was angry, and I decided to chase. I was like ‘Beep-Beep-Beep.’ I thought he kidnapped her so I wanted to just protect her.”

My translation of this is that a friend of his, a Ukrainian woman, was in a car with another man. This angered Artemis, so he chased them down, honking until the other man pulled over. The two of them got into a screaming match on a main street, ending with the woman getting into Artemis’ car instead. The details remain cloudy.2

“The cops came to my house when I was peacefully talking to my friend. Somebody from the witnesses called the police. They just said ‘On your knees! Hands above your head!’ There was eight police cars.”

“Were you drunk?” I asked.

“I was sober. My driver’s license was Mexican and it expired. Also, a DUI is a bad charge.”

“I never expected in my life to be arrested,” he continued, “to be handcuffed, sitting in a police car. I called people but nobody answered, nobody answered. I was praying, I was praying, I was asking God to forgive my sins, because I started to think, this is so bad.”

Artemis was transferred from county jail to an immigration detention facility, only to be told that there was no room for him. His brother eventually paid his bond after a week in custody, so he flew back to New York with an ICE-issued ankle monitor, and a third-degree felony charge for kidnapping, formally called false imprisonment.3

When he got back to NYC, Artemis decided to voluntarily check-in at the ICE building. “I thought, I’m going to be super gucci, I’m not a criminal, I didn’t kill anybody, there’s nothing to worry about. When I came to the plaza, 26 Federal Plaza, the big, scary building, I go and say ‘Nothing basically happened, just a small thing, nobody kill each other,’ and they look and see ‘Kidnapping’ as a pending charge, and they arrest me.”

Artemis was detained on March 18th, 2024; he was not released until January 17th, 2025. He did not win asylum, but was instead granted a withholding of removal–a more limited form of protection. It is a type of fear-based relief that allows the United States to remove him from America, but prevents them from sending him back to Russia because his life or freedom would be threatened there. This was on Halloween day, 2024, yet he sat in MVPC for another 78 days, unaware of a release date. According to his lawyer, Michael Leonetti, a public defender in New York, this happened because he was classified by the court as an “arriving alien.”

“Usually with someone in detention,” Leonetti said over the phone earlier this summer, “they can have a bond hearing with a judge. He wasn’t eligible for that, so we made all these requests to ICE to get him out. They were all denied or ignored, so eventually we had to bring a federal litigation case, a habeas case to get him a bond hearing finally, and that’s how he got released.”

“This was after he won his case,” Leonetti continued. “They detain people for months and months, and it’s like they don’t give it a second thought…I mean, they stole 10 months of his life and it’s not uncommon. There are people who are in immigration detention for years.”

Artemis thinks this is a business practice. “They’re making money on me. They make money on each person. It’s a corrupt system.”

He may have a point. As of February, 2025, around 90% of ICE detention centers are privately owned, for-profit institutions, mostly operated by the publicly-traded prison companies CoreCivic and GEO Group. Both organizations have long histories of nuzzling up to politicians, and their collective $3M of donations to the Trump campaign is paying dividends thanks to the president’s “Big Beautiful Bill,” which allocates $45B for “increased capacity in detention facilities” over the next 10 years. (To watch a movie, Artemis had to pay around 30 cents per minute, which comes out to around $30 per film. It’s no wonder that Salvadorian was working so hard to sell those shanks.)

When Artemis got out in January, over 3 months after his case was won in federal court, he was bussed to Pittsburgh with $5 in his pocket. He gave that to a homeless guy in exchange for a pair of gloves. The rest of his money was held in crypto, which is how he accepted payments for his art while in jail. (The price of Bitcoin rose nearly 70% while he was locked up.)

Money certainly helped, but the stability he had scraped for in New York prior to this debacle was destroyed. “Everything was stolen,” he says of his return. “Everything I owned was stolen. And in my apartment on Wall Street, everything got burned. And in another place, wicked people stole my art. They stole it and sold it. There was a hellish fire. It was burned to the ground. I came back to no paintings, no previous artwork.”

By his tone, it is hard to tell how serious he is. He speaks whimsically, so whether or not the fire was indeed full of flames or merely a metaphor for the trials he has undergone, is unclear. All considered, this detail may not matter much.

“I did not want more troubles,” he said solemnly. “I accepted this, and I let it go. At least I got my freedom back.”

In our first interview, he mentioned that he faced “previous troubles” with the Russian government, implying that he had reason to leave other than the war. My guess is that he was marked as a dissident–for what reason, I do not know. I pressed on this in three follow up communications, and he chose not to elaborate.

Miami-Dade Sheriff’s office could not provide records regarding this event, nor could Broward or Palm Beach County, on the off-chance it happened there. His lawyer declined to speak on the specifics of the case. My best guess is that the records were expunged. Additionally, he and the woman in question still follow each other on Instagram, and, according to Artemis, they are “still friends.”

The charge was dismissed.