The Reading Rumble

A day of amateur boxing in one of America's grittiest cities.

Height and weight aside, Jensen James is different from your average eight-year-old. For one, he is meticulous about his diet, preferring “sustenance over candy.” Dinners are high-protein, fiber-rich and low-carb. Once he finishes, he skips dessert. Also, he is obsessed with his hands.

“He wants to try other sports, but then he says he needs to protect his hands because his hands are his money,” his father, Zach James, tells me. Later this evening, Jensen is set to square off against another eight-year-old, Amir Everett, in a three-round match.

We are in Reading, Pennsylvania, standing in the middle of a sprawling, 1.5 acre parking lot. To our left: A rickety abandoned factory, which served as the headquarters for the Reading Hardware Company before closing down in 1950. To our right: Another massive building which happens to house the East Reading Fight Club (ERFC) on its third floor.

“When I was a kid there was a playground with program leaders that you went to everyday in the summer,” Andre Acuna, the founder of the ERFC and a lifelong Reading resident, told me about the shifting landscape of public resources in the area. “There were sports, local field trips, but budgeting issues 16-17 years ago dried funding up.”

This void in extracurricular activity combined with his real estate acumen served as the genesis for the club.

“We had 6,000 sq feet of nice warehouse space and nothing to do with it,” Andre detailed. “I thought, ‘let’s do something for the community,’ because there was really nowhere for kids to go after school…These kids love each other. They’ll spar with each other, go on morning runs together, push each other. They’ll shed tears when one of them loses. It’s truly like they’re brothers.”

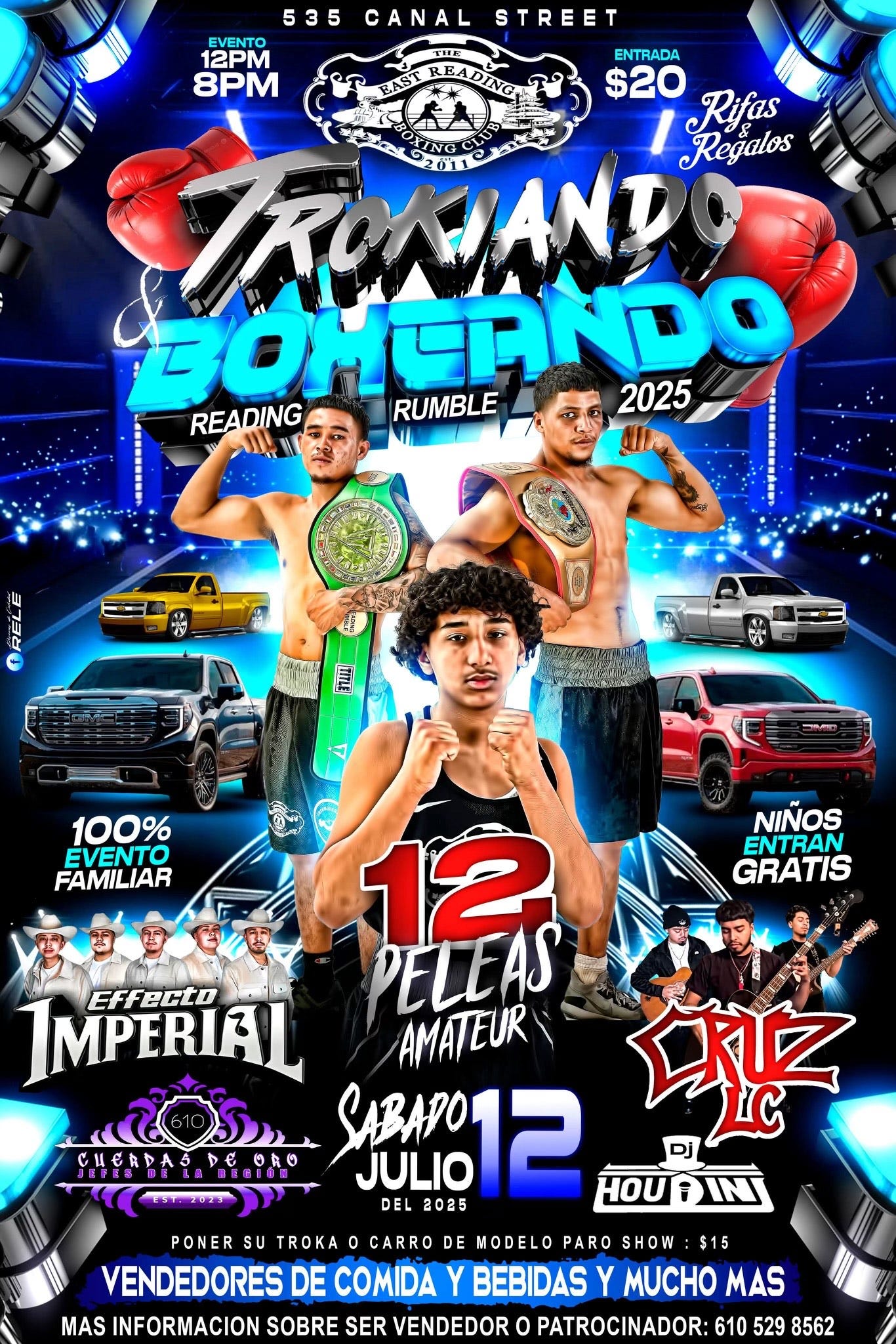

Today, July 12th, marks the second annual Reading Rumble, an amateur boxing event broadly servicing eastern Pennsylvania. The event is officially sanctioned by USA Boxing and will take place on the concrete between the two buildings. Amateur competitors ranging from 8 to 23 will duke it out in front of a crowd of about 150. Friends and family fill foldable chairs, but the bulk of attendees huddle near the ring, shifting from foot to foot. Just over half of the participants fight out of the ERFC, but some have travelled as far as Scranton, PA, and even further still, with a lone teenager making the trek from Ireland.

The fights won’t start until around 5 PM, so there’s time to kill. A perimeter has been established around the space, teeming with tented vendors, exclusively Mexican, selling a variety of tacos, aqua frescas and alcoholic beverages. After perusing some of the wares and opting for a watermelon-based juice, I run into a laborer named Oscar who works for Andre.

Standing around 5’6,” anywhere between 49 and 64 years old, moving at once with feline grace and a hobble born from apparent limb problems, Oscar represents a core demographic within the city of Reading: New York City transplants of Latino descent.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, Oscar relocated to Reading during the early 90s because “the rent was cheaper.” Reading, like other rust-belt cities, used to boast good factory work. Good enough to own a home and retire at a reasonable age. By the late ‘80s, during the second generation of Latino immigration to the area, this began to change.

“It’s not like it used to be–you could rent a house for about $500 a month. Now it’s up to $1500,” he says. “They [home owners from NYC] are buying the houses and then renting them.”

These figures are astronomical for an area like Reading, which does not have much available work. For those who aren’t in health care, the region’s second most popular industry, their bodies often become the means of exchange.

“It’s hard work, not factory work,” Oscar says of the labor required by Deka, a battery manufacturer slightly outside the city that is one of its primary employers. “I wouldn’t want to work there, all that radiation…They pay decently, if you’re happy with $20/hr. But you’re working hard and you can’t control your destiny or future with that sort of income.”

Oscar is diligent about being helpful. He has been doing odd jobs for Andre over the last few months, thinly preventing a descent into homelessness. At 2 PM, as the late-July heat begins to reach an apex, he is beckoned by a group of Puerto Rican teenagers who need help locking the boxing ring into place.

My mental image of a fight weigh-in is a constellation of what I’ve seen on social media. Shit talkers dressed in garish outfits seated about 40 feet away from one another, surrounded by ambiguous posse members. Deeply personal insults, out-of-sight journalists, interview “questions” that are really just fodder for more deeply personal insults. The game within the game is to appear as unbothered as possible. At an amateur boxing event, things are more cordial, if not divorced entirely from this reality. The two sole similarities are a scale and the need to step on one.

Entering the weigh-in room feels like walking into a pocket dimension. The space is one wide hallway that feeds into a 35 x 55 ft rectangular room with low ceilings. Black linoleum vinyl flooring contrasts against Sherwin-Williams alabaster white walls.

I am the only journalist at the event, and the optics aren’t great—not only because I’m in Reading for the express purpose of helping my girlfriend’s dad rearrange furniture in his apartment, but also because I’m recording some of the activity, including, but not limited to, boys taking off their clothes. The whole thing feels much closer to a dozen kids all getting their annual physicals at the same time than anything I’ve seen on YouTube.

Back outside, the sounds of corrido drown out every other sensation, including the heat. Flanked by two acoustic guitarists, an electric guitarist, and an upright bassist, the frontman of the ensemble is strikingly boyish. Clad in a Tijuana jersey and Nike Blazers, he sports an Edgar cut that borders on Lord Farquaad regency thanks to voluminous locks that curl at the ends. His voice is at once elastic and rigid. Notes begin in his chest are held there for extraordinarily long periods, then travel upwards, where they bend and distort through his windpipe. Hearing him sing is a spiritual experience. When I return to my corporeal form and take stock of the parking lot, two imposing figures are walking towards weigh-ins. The Tinoco brothers have arrived.

Martin Tinoco, the younger of the two, is about 5’9” and 150 lbs. He doesn’t say much when we’re introduced, instead sizing me up and downloading soft spots throughout my person that I’m probably unaware of.

A gruff head nod of acknowledgement, fist bump over dap, and eye contact that only breaks when he occasionally surveys his surroundings. His expression is a permanent half-frown. Everything he’s wearing–a tan Dodgers fitted, high-quality sweats, and black Air Max 95s–is crisp, the mark of a man who irons his clothes.

Boxers emanate a particular aura, made manifest in a lazy but deliberate gait–slow enough to admire the scenery, brisk enough to avoid gawking. Their heads are on a swivel, scanning possible escape routes and surface terrain, instinctually mapping out the vectors of confrontation. Boxers are also the most serious athletes I’ve ever interacted with: A side-effect of a sport that speedruns CTE and is about sixty years removed from its cultural, financial, and spiritual peak.

Julio Tinoco, the older and larger brother, measures out closer to 6’1” and 180 lbs. His temperament is warmer, offering the semblance of a smile as we meet. We soft dap, a gesture that feels intimate as opposed to meeting Martin, whose boundaries regarding physical touch are limited to his knuckles.

Both brothers carry the gravitas of marble statues: Feet fixed, posture perfect, extraneous movement near-zero. I’m convinced that if I had a stethoscope, measuring their heart rates would yield the same BPM as Navy Seal snipers.

Prior to being introduced, their toughness has already been explicated to me by Zach James, ERFC’s head trainer, in several roundabout ways. For example, they both have taken last minute fights against heavier opponents:

“[Martin] wasn’t supposed to fight that day. He was in Scranton to support Julio. They had a guy with no opponent and Martin said ‘Alright, I’ll take it,’” James says. “We had to get him gear. Buy him stuff that day, so he could fight…And Julio did the same thing. He was 180 and fought a guy who was 200 lbs,” he continues. “They are not afraid of anyone…They proved they can be the smaller guy and walk out with wins. They are two very Mexican-blooded brothers.”

When I ask Julio about moving up weight classes to fight heavier opponents he is less severe, as Zach has the tendency to describe anything boxing-related with the same intensity as someone who just escaped a death camp:

“You’re hitting them and it feels like your punches are doing nothing,” the elder Tinoco brother said with a slight grin. “He hits you and you feel it. Even if it’s just a punch to the gloves.”

By day, the Tinoco brothers are landscapers. By night, they train six to seven days a week in hopes of reaching the professional level. Martin is 21 and Julio is 23, which may register as relatively old for the amateur circuit, at least for aspiring professionals, but Andre maintains that your boxing age is measured only by how long you have been seriously training.

The duo carved out reputations as premier brawlers in their hometown of Fresno, California. It started as daily scraps in their household. “Everyday we would find something to fight over,” Martin said.

Living room tussles, unable to be contained, escaped outside onto pavement. Even with friends around, it became nearly certain that Julio and Martin would trade blows at some point during the day. “Friends started bringing gloves out because it would get pretty serious,” Martin explained.

When other kids in the neighborhood caught wind of the show they also tried to jump into the fray, only to become spectators. “We’d take the gloves onto the street and box other kids. It would always end with us [the brothers] fighting each other,” Julio continued. It wasn’t until a cousin told them to go to the gym that the idea of professional fighting began to germinate.

As I go from location to location, Andre and Zach stay by my side, telling the fighters that I am a writer who will be asking them questions, and that they should answer thoughtfully. It is the sort of near-threat you receive before a substitute teacher rolls in.

Approaching people to speak on record is harder at this event than anything I’ve ever reported on. Without the safety net of a “media” pass or some other talisman hanging around my neck justifying my presence, speaking to attendees is like hitting on a stranger at a food truck festival. This isn’t an event journalists cover, nor is it known outside of immediate boxing circles.

I also stick out more than usual. My tattoos are whimsical, whereas the dominant ink choices are rooted in photorealism: Spartans or other gladiatorial figures, apex predators, and homages to Philadelphia in the form of highway signs. There is nothing funny about putting something on your body forever. The most common physical build is that of an upside down trapezoid: Wide necks, lats, and shoulders, with the rest of the body narrowing towards the feet. I’m lanky and wiry: A sophomoric Spongebob trying to gain entry into the Salty Spittoon.

Inside the ERFC, the training room reeks of testosterone. A couple fighters slated to face off on the earlier side of the event, Jensen included, take turns drilling footwork and hitting the heavy bag. The master wall in the gym is adorned with floor to ceiling mirrors, which reflect the same unchanging gaze regardless of who is boxing in front of it. Others sit with their legs up in front of an industrial-grade fan, picking at styrofoam plates of fried chicken, BBQ, collared greens, and mac-and-cheese. Youngboy songs are interrupted only by Kodak Black.

Isias Rios, the third headliner who appears on the fight flyer, is perpetually moving on the balls of his feet. He cannot remain in one position for too long, covering ground like a distance runner even in his social interactions. “I was really small and my mom wanted me to start boxing because I didn’t know how to defend myself,” he tells me. “She was a little scared for me.”

Rios is a 15-year-old who looks even younger than his age, stands about 5’6,” and sports a moppy head of black, ringlet curls. Before meeting him, I had already heard about his high-octane fighting style: always on the offensive, overwhelming opponents with volume to make up for his stature.

His weightless charm is infectious, a stark contrast with the majority of everyone present. If he isn’t play-punching friends, he’s shadowboxing near them, weaving his way around training equipment that bears a resemblance to the same gizmos you’d find in the pages of a Dr. Seuss book. He is one of the top prospects in the ERFC and Andre envisions a spot on Team USA in his near future.

“I got beat up by a girl,” Rios recalls, when I ask him about his first sparring session. “I was kinda scared to hit her, she knew how to box and I didn’t. Then she started beating the shit out of me.”

With an hour to go, Rios learns his opponent is a no-show. Months of training and mental preparation have no release valve. Extended family members two hours away from Reading drove in to watch him, but Rios attempts to play off the disappointment. Fault lines threaten to form across his baby face. Despite already generating the most kinetic energy in the vicinity, Rios’ activity cranks up. Pent-up frustration is repurposed to work the mitts with Jensen.

As golden hour sets in, the crowd congregates around the ring in folding chairs. I’m seated behind the family of Amir, Jensen’s opponent, who all sport black t-shirts bearing images of the eight-year-old boxer in the vein of a No Limit mixtape cover.

It quickly becomes apparent how much pressure there is on Jensen. He is smothered with encouragement not only from his dad, who helms his fight corner, but nearly every fighter in the ERFC, who bombard him with their own separate, motivational speech, spittle flying into his face. These aren’t solely amateurs either. David “Dynamite” Stevens, a professional boxer who came out of the ERFC and is currently signed to Golden Boy Promotions, whispers something in Jensen’s ear, too.

Jensen begins the fight on the offensive, staying close to Amir to hit him with a barrage of jabs. Without panicking, Amir keeps Jensen at bay with his length and manages to land jabs of his own. You can almost see Jensen get taken out of the fight mentally when his primary plan of crowding his adversary fails. The volume also begins to drain his gas tank and taking shots to the face does not help. The crowd is electric for this initial fight and louder than it will be for the rest of the night.

By the final round, Amir is clearly the victor, stalking Jensen around the ring and hitting him with the occasional jab or hook. Cries from Amir’s family and from Zach can be heard above everything else. “Get out of the corner,” Zach yells as time winds down. “Jensen, I need you to keep your head up!”

Both father and son look crestfallen after Amir is pronounced the winner.

The lone Irish boxer exudes a neutral demeanor on his handsome, rosy-cheeked face. While other fighters bear some emotion during their bouts–excitement over landing a punch, surprise at getting punched, anguish at losing–he is unconcerned. Approaching the ring draped in an Irish flag, he stares into the camera of his videographer blankly. It’s as if he has never seen the technology before.

There is an Irish boxing gym in Scranton that has satellite locations in Ireland. Fighters from the motherland are sent stateside to compete in amateur matches across the east coast. Andre highlights the no-nonsense temperament of everyone associated with the operation: “Those guys are training with one thing in mind–to go pro.”

He is the most technical boxer of the night. Every 1-2 is thrown cleanly and on target. Each step he takes toward, away, and around his opponent is intentional, constantly probing for an advantage or positioning himself to capitalize on a mistake. At one point he connects on a body shot that sounds like a metal pan being smacked by a wooden spoon. The match ends in a unanimous decision with him holding the Irish flag high above his head.

By the time the Tinoco brothers are ready to fight, the sun is about to set. Martin is surgical in his exhibition, giving up no ground and often pressuring his opponent. He stays low and keeps his left hand in guard, while his right arm hangs loosely at his side, winding up before every feint or overhand. He earns a decisive win, taking almost no damage.

Martin is the most locked in participant at the day’s event. From the way he regulates his breathing to his upright posture, he projects a willingness to die in the ring if needed. Andre tells me that during Martin’s first amateur fight, which he took after three months of real training, he was knocked out cold. He didn’t take another fight for over a year due to injury but also because he “knew [he] had to get better.”

“I always felt like I was skilled, so it’s crazy to me that I lost. But I learned so much after,” he told me. “I didn't train 100% before because I didn’t know what to expect. I didn’t have the experience. But I was humbled after that fight.”

During the main event, Julio gets knocked down in the second round while peppering his opponent with heavy hooks to the obliques. It’s the first time he’s touched earth in his fledgling career. He delivers the fight of the night after bouncing back from getting rocked.

Part of amateur boxing’s appeal is the exhibition of high-level skill: Athleticism, feints, footwork, striking, punching volume, combinations, it’s all there. But blows don’t often do real damage, especially in the younger age brackets. Julio and his competitor–a white boy built like a D1 slot receiver who trains out of a cutthroat Philadelphia gym–are some of the only fighters throwing punches that could break bone and separate skin.

They grunt louder and louder with each punch thrown. After getting knocked down, Julio is aware he has to be aggressive for the rest of the match in order to land enough strikes to tip the fight in his direction. Abandoning defense, he throws a constant string of overhand straights at the expense of getting countered. He manages to land enough big punches to bloody his counterpart, who is leaking red from his nose. Despite getting hit in the head over and over, he refuses to go down.

By the end of three rounds, both fighters have given everything. They are exhausted and flushed, half-holding their gloves in the air to rapturous approval from the crowd. Julio did enough to sway the judges back in his favor and is declared the victor.

Martin stands next to his brother, finally smiling. He seems relieved. The pressures of his work and craft can be discarded, at least for now.

“Sometimes you’re in control and dominating, and you’ll be thinking the whole time,” Julio told me earlier. “Other times it turns into a brawl. Everything goes out the window, you’re swinging and just trying to land. You just want the fight to end.”