Basketball, Blandas, and Bulls

In Oaxaca, Mexico, El Güero discovers the region's deep love of hoops.

It’s the semi-finals of the San Antonio de Padua Festival’s basketball tournament in Hidalgo Yalalag, Oaxaca, and Juan Mixe twisted his ankle. The wavy-haired, undersized guard just caught a pass while cutting into the lane. In one full extension, Juan spun a layup high off the corner of the wood backboard. While the ball twirled in the air, Juan’s body met the broad chest of a help-side defender hungry for a highlight block. Juan grated clear across the concrete floor, his eyes never leaving the hoop until he knew the bucket was good.

Mosquitos are unrelenting under the covered ceiling, outdoor basketball court. The festival crowd is growing impatient. The Jaripeo-bull riding of the day is finished, and festival rides are closed for the night. All that’s left to see is a champion for the main event of the town’s biggest yearly cultural festival. Each foul call is met with emphatic whistling, only further incentivizing a more physical game.

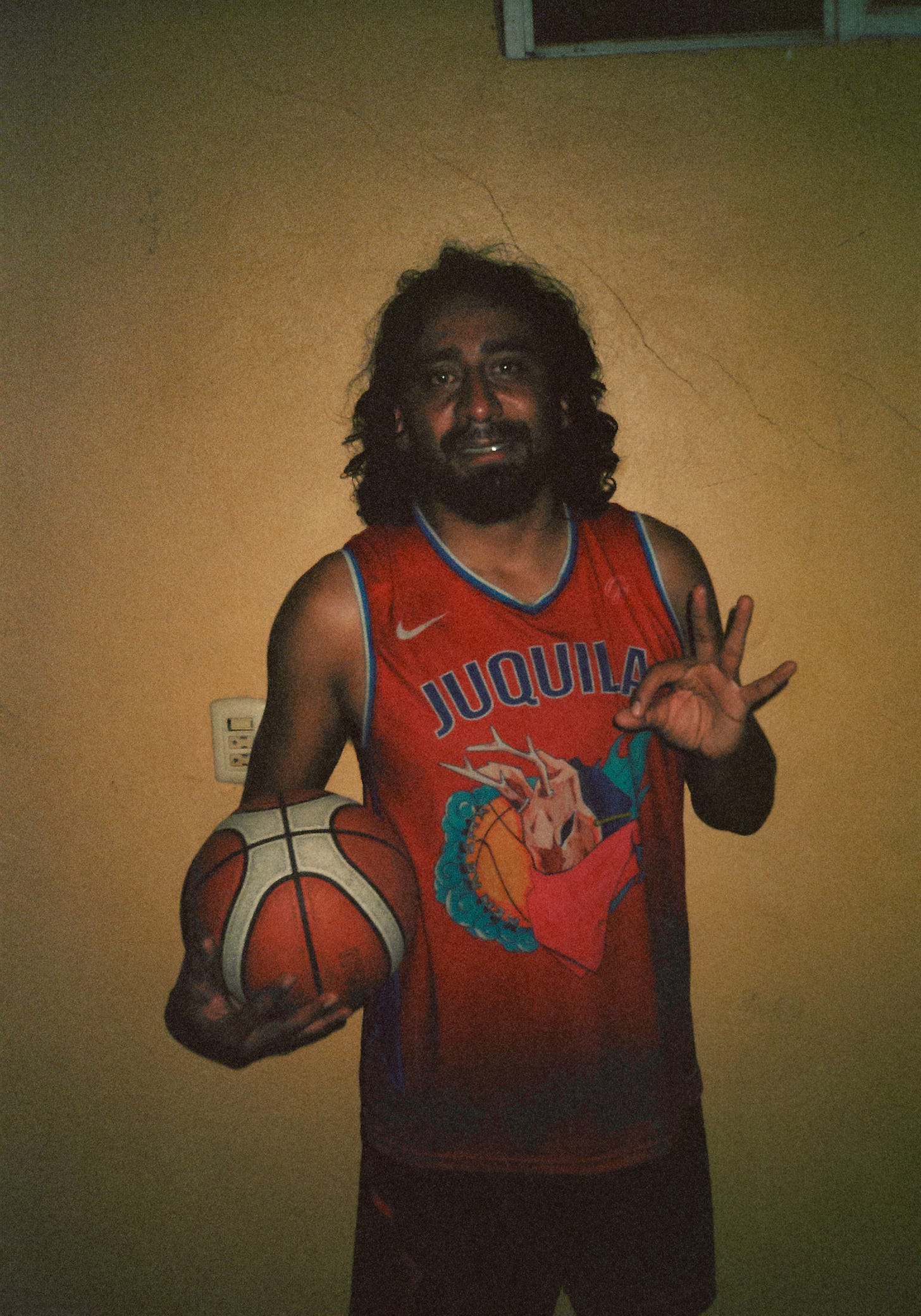

The veteran guard takes a second. He winces. He grunts. He reties his shoelaces a little tighter, before hobbling over to the free throw line. While some continue whistling, others begin chanting his name. Juan buries the and-one and limps back to play defense. There are no substitutes on his team. Any extra players would only further split the potential $20,000 peso winnings for the champion. During the work week in Oaxaca City, Juan Arturo Oliveira-Espina, 32, may be an agro-industrial engineer for the federal government, but in the mountains of Oaxaca, “Juan Mixe” is a star.

Juan Mixe’s legend around the festival comes with kids asking to take pictures while he stretches before the game. But Oliveira-Espina laughs at the idea of celebrity. He says his game is a pass first and defensive-oriented play–he doesn’t take over a game like his childhood idol Michael Jordan. Sure, he’s still the leader, but perhaps the best quality of his team, San Juan Juquila Mixe, is their willingness to share the ball.

“We’re pure family. We defend each other, if someone gets hurt, we take care of them,” Oliveira-Espina tells me after his team wins the game and awaits the tournament final. “Almost all of us [on the team] are cousins. Every time there’s a festival in Oaxaca, there’s going to be a basketball tournament. And our team probably plays in about 10 tournaments a month.”

Oliveira-Espina’s nickname, “Juan Mixe,” is a reference to the indigenous Mixe language spoken in the Sierra region of Oaxaca. It’s a name that comes with the honor of representing both his hometown and his indigenous roots. Juan’s name is spoken with hushed reverence or jeers from fantatical haters. While every weekend in Oaxaca brings basketball tournaments with ever increasing prize winnings for the players, the sport is in a long lineage of pride in each community.

“For us it goes back a long way. My grandparents even played,” Oliveira-Espina says. “My parents were Michael Jordan fans. They shaved my head. I wanted my hair long. My mom, who didn’t even know much about basketball, said, ‘no, like Jordan.’ It’s something that sticks with you, but it’s something very beautiful.”

While many Oaxacans identify with the lineage of their town’s indigenous community and language, my teammates from the hometown Yalalag, call me, “Camarón,” the Spanish word for shrimp and approximating my actual name, which is awkward for Spanish speakers to pronounce. Those who don’t know me just call me, “güero,” essentially Spanish for “white boy.” It’s a scrappy team, made up mostly of guys over 40, who also play in the “veterans” division.

As the crow flies, Yalagag is only about 30 miles away from San Juan Juquila. But the Sierra de Juarez mountain range and miles of winding semi-maintained roads stand between them. Yalalag is home to the Zapotec indigenous community, with a different language, giving our team its unofficial name–the Zapotecos.

I arrived three days earlier at the start of the 2025 edition of the festival of San Antonio de Padua held annually in early June. My friend Alex, a Oaxacan I met at a pickup run in Mexico City, insisted I needed to go to a festival in his home state. He texted some of his friends from his village, who connected me with the local tournament organizer, Adelfo. A week later, I was taking the ten hour night bus to Oaxaca City. Luckily, Adelfo also ran a cab business in town and arranged for an affordable ride up the mountain.

Packed two people to a seat in a shared taxi, we rode nearly four hours through the foggy foothills that only seemed to get greener and wetter as we left the valley. Maguey and cactus lined the sides of the highways, at times we’d drive through three towns and the only other traffic were three-wheeled mototaxis struggling to scale a steep graded highway. As the shared cab arrived into town, the last few miles switched from two lanes of traffic to one, as a highway improvement project sought to repave a rough stretch of road.

I met Adelfo outside the Hidalgo Yalalag administrative building, along with two grade school teachers who helped him organize the competitive sports side of the festival. A Catholic church stood as a centerpiece at the end of the main street. Directly outside the church, vendors set up tents in front of homes and store fronts, slinging a range of wares. Various family mezcal distilleries offered samples. A man’s mini-leather goods-emporium sold cowboy hats, cellphone holsters, and belt buckles. The local sneakerhead posted up with a pile of basketball shoe boxes across the street. After browsing, one of the teachers, moonlighting as a cabbie, gave us a ride to the stadium down the road in his mototaxi that had a decal of Bugs Bunny wearing a Michael Jordan jersey.

Club Deportivo Yalalag kicked things off with a futsal tournament on the town’s multiuse basketball court. The crowd was sparse. Children marched the cobblestone streets with brass and woodwind instruments playing Tambora music, often with an adult pacing in front, letting off fireworks. The town offers three free meals a day for all attendees—carnitas tacos with consume, traditional Oaxacan moles, and spicy shrimp soups. With accommodation sold out far in advance in these small towns, tournament players are offered bed rolls and space to sleep in the classrooms of a local elementary school. Adelfo, however, led me up into the hills overlooking the town square where they had a coveted extra bed in his family home.

The festival, and the accompanying basketball tournament, is a full community affair. When the torrential downpour almost entirely flooded the basketball court and put the tournament on pause, Topiles, community police forces made up of unarmed young men in indigenous communities throughout Oaxaca, jumped to the task of digging trenches, diverting rainfall with metal siding and trash cans, and using push brooms to get water off the court. All that remains of the flood are a few slick spots at the corner three, a slight hazard for any spot up shooter. Many hands and some makeshift flood engineering brought the basketball back within a half hour.

Basketball’s history in the mountainous region of the Sierra Norte began in the 1930s during an era of land reforms following the Mexican Revolution (or 3rd Transformation) of the 1920s. This all part of the newly minted Mexican Constitutions attempts at land reform and the creation of communal space after the feudal dominance of mostly European land owners of indigenous peasants pre-revolution. The newly democratized Mexican government made concessions to organized indigenous communities in the form of infrastructural development which came coupled with Spanish literacy programs–an early attempt to foster a new national “Mexican” identity.

“The topography is different in Oaxaca,” says Jesús Pacheco-Reyes, 65, who has coached youth squads in Villa Alta, Oaxaca for more than 30 years. “While kids were learning soccer [in other parts of Mexico], there weren’t enough large spaces to build soccer fields here. Basketball has always been the most important. In the 1930s, a group of [Spanish] teachers arrived, and that was the sport they started practicing there in Villa Alta, and it spread little by little.”

The fledgling democratic state built sports complexes with covered basketball courts that double as town center meeting spaces and dance or concert halls. With a high illiteracy rate in the poorer and underdeveloped states in southern Mexico, the government sent teachers, who in turn brought basketball.

Outside of the cobblestone streets, Michelin Star restaurants, and Mezcalerias of the state’s capital city and coastal resort towns like Puerto Escondido, Oaxaca is still one of the poorest regions in Mexico. A majority of people live below the national poverty line, and nearly a quarter are considered to live in “extreme poverty.” A large portion of the local economy is based on remittances sent from family members working in the United States, and many young adults in their prime basketball years have immigrated to the US.

Even as the US border grows more increasingly militarized, with more families separated for longer periods of time, the basketball tradition in Oaxaca continues. Families send remittance money to help organize the tournament, build bigger prize purses for players, and in some cases send second or third generation Mexican-American descendants back to their family’s hometowns to compete.

Friday is the first day of basketball tournament play. It’s reserved exclusively for the children’s divisions. Hundreds of kids from surrounding towns played games from 9am until long past sundown, breaking for their three complimentary meals. Pacheco-Reyes coaches every level of youth ball for his town of Villa Alta, who are always among the best in tournament play. Games are briefly interrupted for a Catholic procession and full marching band crossing the court towards the Jaripeo ring adjacent to the stadium. Children in their colorful basketball uniforms race each other to climb up the wooden fence structures like a jungle gym, jockeying for a view of the priest blessing the ring for the safety of the bull riders.

“It’s a cultural exchange.The kids play, they learn, they get to know other people’s traditions,” Pacheco-Reyes says. “My philosophy is that children need to have fun. Having fun is what opens us up to learning and becoming good human beings. Basketball is part of the kids’ education, it’s an opportunity for so many to get a chance to continue studying.”

A teenager wearing a Slayer longsleeve tells me he wants to practice before starting university as a computer science student in Guanajuato, Mexico. Earlier in the day, he played for the highest level youth team for Yalalag, but lost to the undefeated future champs. He sees basketball mostly as a pathway for his education, but is frank about some of the unfairness of the competition.

“[That team] won the Benito Juarez Cup,” he says. “They recruit and pay players. But at least they’re all from here. The team they beat flew players in from the United States, their coach was speaking only in English. Some of the kids didn’t speak any Spanish at all.”

Hosted by the community of San Juan Atepec each March, the Copa de Benito Juarez is the largest of the Oaxacan tournaments. Named after Oaxaca-born Benito Juarez, the first indigenous president of Mexico, the Copa attracts the most teams by offering some of the highest payouts to winners, and the most glory to bring back home.

“In some communities it’s like a business,” Hidalgo Yalalag team captain Eddie Cosijopi Jaimez-Aquino, 43, says. “I started playing in tournaments when I was nine and they’ve always been tough and competitive. At first [prizes] were a bull, a pig, a horse. I won a donkey once. And people would buy it back from you right there. Little by little, they started giving out cash prizes. Well, that’s when the party started to fade away a bit. Basketball mercenaries started to appear.”

Broadly, basketball has grown exponentially in Mexico. The country saw an influx of international investment from the NBA in the form of the NBA Global Academy in the central Mexican state San Luis Potosi, and even a G-League franchise in the Mexico City Capitanes. Mexico’s own growing professional league brought teams to the more industry rich northern Mexican cities and financial capitals like Mexico City. Rosters typically are about half domestic born players and half guys you might remember from March Madness’ past. (Ángeles de la Ciudad de México featured Oakland University’s cold-ass-white-boy Jack Gohlke on last year’s roster.)

“There’s always a lack of organization and support from industries and government here,” Pacheco-Reyes says. “There’s talent to make it happen. And of course, there’s lots of basketball fans, just no support.”

The most powerful institutions in the sport don’t seem to be on the horizon either. Last November, the NBA announced that they would close their international development academies in Mexico and Australia in the summer of 2025. Troy Justice, NBA’s head of international basketball operations, called the decision a “strategic move,” adding that the league would be “changing locations and reallocating resources to be in places where we can help provide opportunities to more players in underrepresented countries.”

Speculation from league reporters indicates Abu Dhabi is the most likely destination for the next academy. This October, the New York Knicks and Philadelphia 76ers are set to play two preseason games in Abu Dhabi’s new arena, a move that speaks more towards the increasing international financialization of the NBA, rather than “international player development.” In 2023, Qatar became the first Sovereign Wealth Fund to purchase the current league maximum 5% stake in the Washington Wizards. But while oil money might feel like a safer economic bet for the league, the basketball culture in Oaxaca and the rest of the mostly indigenous southern Mexico seems largely undeterred, mostly because they never benefited from the US development dollars.

“Wealthy people aren’t really interested in training the people who truly serve the community,” says Jaimez-Aquino. “Look at the [Mexican] national team. It’s all players from Mexico City or the north. Oaxaca doesn’t have wealthy investors like in other states.”

Walking around town throughout the week, people stop to ask me how I found my way here and offer me beers that I quickly learn I’m not allowed to turn down. One guy instructs me to join him in a video for his Facebook to say, “Chinga tu madre Trump, Chinga tu madre Cruz Azul, Vamos Club America!” before his former bull riding father hands me a bottle of mezcal and instructs me to take a swig. “It’ll help with your nerves in your next game, güero,” he says.

I can’t help feeling like the level of friendliness towards a gringo stranger feels unwarranted. That same week, Donald Trump had just sent in the National Guard to Los Angeles in an effort to quell anti-deportation protests and bolster the efforts of ICE. Protests were only escalating to combat aggressive ICE raids in early June. The majority Latino community had resisted La Migra, some throwing rocks and physically blocking ICE vehicles while the federal agents beat and even ran over protesters with their SUVs. It’s a city where nearly everyone I speak with currently has family or friends living. Multiple people tell me they have family that usually would attend this festival but are not because they are afraid they can’t return to the States after.

I chat with a handmade huarache shoemaker who sees my basketball shoes and asks if I would be willing to bring back a pair of Nikes to trade for one of his. I tell him I would try to bring some if I can make it back next year, and a guy walking by stops.

“Why are you here, gringo?” the man says.

“I wanted to learn more about your festival,” I say. “I play a lot of basketball back home and my friend wanted to show me how you all play here.”

“Well you can come here all you want, walk on our land, eat our food, and nobody stops you,” he pauses to spit. “But I can’t go to where you’re from. I’m not welcome.”

The man walks off towards the festival center without waiting for a response. The huarache maker tells me that the guy is just a crazy drunk, and apologizes profusely for him. I tell him it feels strange that more people haven’t said anything like that. He may be drunk, but he’s right.

On Saturday, players from the eleven participating teams in the top billed Open-Category get shots up while waiting for sign-ups to begin. I walk with team Yalalag up to the cafeteria for breakfast. Our team is made up mostly with the same guys who play together in the Veteranos (40+) division, plus a 20-something cab driver and myself. Eddie is the undisputed leader, taking on a player-coach role as he calls out defensive assignments and frustrated pleas to get the ball into the high post on offense. They give me a maroon and black jersey that says “Gladiators.” Only one other teammate sports the jersey, with the rest wearing slightly different versions of yellow and black jerseys with the town name or no jersey at all.

At 6’1”, I’m one of the taller players in the tournament, and most of the kids expect me to be able to dunk a basketball. But a year and half post-ACL surgery, I ultimately disappoint. Still, I’m asked to play center on offense and one of the two posts in our 1-2-2 zone, the standard defense for all pickup basketball I’ve played in Mexico.

The ubiquity of the aggressive zone defense in Mexico instills a unique set of principles: fast pace, maintain good three point spacing, make the extra pass, fight for the ball on rebounds. If this isn’t structurally reinforced by defensive strategy, the referees are not forgiving to anybody trying to beat the defense by their dribbling prowess. You will get hacked, and while you throw your hands up looking to the ref for relief, the other team’s already made the outlet pass for a layup on the other end. More than anything, the crowd seems to feed off anyone seen as complaining, whistling at nearly every pause in the action can overtake the student band brass section. The whistling is often in an iconic Mexican cadence, a euphemism for the vulgar phrase “chinga tu madre.” It’s brutal, beautiful basketball.

“The referee isn’t going to call anything on you, he’s happy as long as you’re not hitting anyone,” Oliveira-Espina says. “The fans will let you know what they think. And it’s personal because it’s their family on the court. If people boo and jeer you because you’re playing in a region far away, it’s just part of the fun. It makes the stakes feel bigger, you know?”

Our first two games took some adjusting to fit into the flow of our team’s offense. Eventually, I settled into a role of scoring on baseline cuts and passing the ball out to shooters. However, in our fourth game, we faced tournament favorites from the mining town of Natividad. The team is led by a father, his two sharpshooting sons, and the tallest player in the tournament, a 6’5” (6’7” in shoes) player easily leading in blocks and assists off outlet passes through the first few rounds.

We started out hot. Eddie banked in a three, and we managed to score on a few lucky hustle plays and offensive rebounds. To all of our surprises, we were up by six points at halftime. The hometown crowd, who had been rooting for the out-of-town favorites based on their reputation earlier in the tournament, started to believe in the underdog Yalalag’s chances. The second half started out much the same. I caught a pass around the free throw line, dribbled hard to my left, and drilled a scooping hook layup over their 6’7” guy. I ran down the court holding my hand low, for the first time in my life making the “too small” symbol–time out Natividad. The crowd erupts in whistles and laughs for the güero.

Ultimately, the better team adjusted. Natividad returned from timeout running a man-to-man defense. All our cohesiveness and teamwork was forgotten. Our lead evaporated, while I tried to think of what the Spanish phrase for “pick and roll” is. Trailing by two with ten seconds left, Eddie found a wide open shooter, whose prayer was met by an unforgiving, hard rim. A fourth place finish brought on a chorus of teasing whistles, louder than the buzzer. It’s pure basketball.

We spent the first round of post-game beers dissecting what we could have done differently together. There was no consensus, but nobody seemed too disappointed in our differing stories. By the next round, we’d already moved on. Somebody’s cousin from the crowd wanted to get us a third round as a consolation prize. I only noticed another game had ended when the team from San Antonio joined us on the cement bar patio. Their third place finish warranted Eddie to buy them all a drink.

Compared to my adult rec league games, where there is maybe one uninterested girlfriend sitting on the middle school gym bleachers, the game couldn’t have been bigger. There’s no official count, but it seems like there were more people in attendance at our semifinal match than I saw at the pro league game in Mexico City. Admission is free, the beers are cheap, there’s a live band, street food, and a mountain view on the other side of the bar.

The championship was not particularly close. San Juan Juaquila Mixes dominate, the hobbling ankle of their lead guard remaining intact enough to pull them across the finish line for the $20,000 pesos. The trophy ceremony lasted another twenty minutes, before the town moved on to turn the court over for cumbia dancing. The next day, the team will do it all again in the Veteranos (40+ division). Eddie asked if I would join but I told him I’m not old enough. They wouldn’t need me anyway. Sunday is the last day of the festival to San Antonio Padua and it’s decisively more chill. By that time the next day, Yalalag will have taken home gold. The game may be slower, the manic energy of playing twenty feet away from guys wearing sumo suits getting blasted by a bull may have gone, the payouts may even be less. But for the hoopers continuing the legacy of basketball in the mountains of Oaxaca, there’s always more hoops.